The Plank Road

Picture yourself back in 1918 trying to cross the burning desert of Imperial County. You reach the treacherous Imperial Sand Dunes and face the challenge of a seamless ocean of sand. With relief and anxiety you begin to ascend the first dune on the Plank Road. The heat, swirling sand, and jarring ride across the rough planks makes you nauseous, but you are grateful since this new route offers safety and cuts many hours off the adventurous trip across the desert.

The story of the Plank Road began with the era of automobile transportation and the growing rivalry of two Southern California cities, San Diego and Los Angeles. Just as railroad towns owed their financial well-being to rail commerce, so would communities linked by good roads benefit from the automobile. Civic and business leaders quickly perceived the benefits of bringing routes and roads to their communities. Having lost a bid to become a terminus for the transcontinental railroad, San Diego was determined to beat Los Angeles to become the hub of the Southern California road network.

Chief among the promoters for San Diego was businessman and road builder "Colonel" Ed Fletcher. Fletcher sponsored a road race to demonstrate the best route between Southern California and Phoenix, Arizona. A Los Angeles newspaper, the Examiner, issued a personal challenge to Fletcher, and a race was set for October 1912. With a 24-hour head start, an Examiner reporter would travel from Los Angeles to Phoenix, and Fletcher would proceed from San Diego, each attempting to demonstrate the feasibility of his route. Fletcher chose a route through the Imperial Sand Hills, and with a team of six horses to pull his automobile through the sand, Fletcher won the race in 19 1/2 hours!

Two developments contributed to the success of Fletcher's plan. First, Imperial County Supervisor Ed Boyd joined Fletcher in advocating the Sand Hills route as a direct east-to-west course between Yuma, Arizona, and San Diego. Second, the federal government and the States of California and Arizona approved construction of a bridge across the Colorado River at Yuma. In addition, San Diego announced plans to hold an exhibition celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal in 1915, an event designed to lure thousands of visitors, many traveling by automobile. Could a reliable way be found to cross the shifting sand dunes?

With local newspapers supporting the plan, Fletcher raised the money to pay for 13,000 planks plus the freight to ship them from San Diego to Holtville, California. Meantime, Boyd and his constituents persuaded the Imperial County Board of Supervisors to appropriate $8,600 toward construction expenses. L.F. (Newt) Gray, a local man chosen to supervise road building, sank a well at the western edge of the Sand Hills and found water. Gray's Well, as the spot became known, served as the work camp.

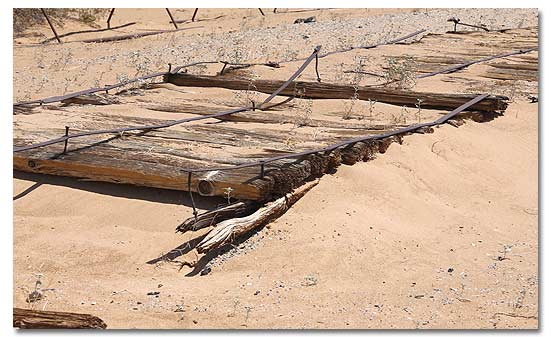

Amid great fanfare, the first planks were laid on February 14, 1915. For the next two months, a combination of volunteers and paid workers hauled lumber and laid down two parallel plank tracks, each 25" wide, spiked to wooden cross pieces underneath. The wheel path floated across 6 1/2 miles of shifting sand east of Gray's Well. Work ended on April 4, 1915. A week later, the "glad Hand Excursion," consisting of 25 cars loaded with over 100 riders, gaily traveled the Plank Road and declared it a success.

Traffic, however, quickly took a heavy toll on the planks. Battered by the passing cars of tourists and farmers, the road was splintered further by maintenance crews who uncovered the wooden road with mule drawn scrapers to clear it of drifting sand. Still, Fletcher and Boyd had proved that a road was feasible, and motorists had demonstrated the necessity for a good road. In June 1915, the California State Highway Commission assumed responsibility for the Plank Road as part of the road system linking Southern California with Arizona.

With more funds, manpower, and equipment than the pioneer road builders, the Highway Commission built a new Plank Road in 1916. Engineers abandoned the double-track plan and designed a roadway of wooden cross ties laid to a width of 8 feet with double-width turnouts every-1,000 feet. Sections 12 feet long were preassembled at a fabricating plant set up at the railroad town of Ogilby, California. Completed units, which weighed 1,500 pounds each, were transferred onto wagons by means of a derrick specially designed for the task. Out in the dunes, workers prepared the roadbed by leveling the sand with scrapers. Sections of the Plank Road were then lowered into place using a crane.

Plank Road upkeep proved difficult, and a permanent maintenance force was stationed near Gray's Well. From 1916 to 1926, crews of workmen struggled incessantly against nature to keep the road passable. Hard winds blew drifting sand across the road an average of two or three days a week, rendering the road nearly impassable about one-third of the time. The crew routinely worked the road with Fresno scrapers hitched to a team of draft animals, and travelers huddled in their vehicles while the sand swirled around them.

Crossing the Plank Road was both an adventure and a trial. Pulling off the road onto the turnouts so that others might pass tried the patience of motorists. Traffic jams in the midst of desert vastness were not uncommon. On one occasion, a caravan of 20 cars encountered a lone traveler going in the opposite direction.

Whether through timidity or stubbornness, the driver refused to back up to a turnout behind him. Finally, the party took matters in hand. The men lifted the car and set it on the sand, while the women proceeded to advance the caravan. When they were past, the car was lifted back up on the road, and all continued on their way. Turnouts along the Plank Road were marked with old tires mounted on high posts to make them visible from afar.

Then there was the road itself. Holtville resident Ida Little reminisces that, "You just bumped across it, and it was bumpy! I always said that going across the Plank Road was as good as having a chiropractic adjustment." Ronald Layton concurs. "It was pretty rough, but the ride was in a cadence because the boards were all ten inches wide, if I remember right."

Despite the discomfort and outright danger of crossing the Plank Road, former travelers still recall with amusement the feeling of high adventure that was part of the Plank Road experience. While the road opened up a valuable trade route for Imperial Valley farmers and townsfolk, riding across it also became a favorite winter recreational activity.

High school chums, church youth groups, and families often jounced across the road to Gray's Well with a picnic lunch or a camp stove for a steak-fry. In fact, desert parties were so popular that Gray's Well usually resembled a campground during the winter months. Newt Gray obliged travelers and desert party groups alike by stocking a small, tin roofed store with emergency provisions and cold drinks. During Prohibition, more potent liquids reportedly were available to slake one's thirst.

The days of the Plank Road were numbered. The twin headaches of maintenance and traffic flow required a better solution. Non technical suggestions ranged from digging a tunnel under the sand to elevating a structure above it. The State Highway Commission received unsolicited advice, while Highway Engineers studied the problem of attaching a traversable surface to an unstable roadbed. In 1924 the Commission tested a new, improved Plank Road which would permit two-way traffic to cross the dunes.

From 1923 to 1925, engineers monitored the movement of sand dunes adjacent to the Plank Road and tested various surfaces. After concluding that hills of sand over 100 feet high moved very slowly and only the lower dunes moved rapidly, it was determined that a permanent pavement road was indeed possible providing the grade was sufficiently raised.

With an engineering solution at hand, the Highway Commission decided on an asphaltic concrete surface constructed on top of a built-up sand embankment. The new road, 20 feet wide, officially opened on August 12, 1926. Praise for the highway was mixed with a certain nostalgia for the primitive wooden contraption it replaced. After all, the Plank Road had added a bit of spice to life in the Imperial Valley.

Despite pleas from local residents for preservation, the Plank Road began to disappear: a section to the Ford Motor Company for display purposes, another section to the Automobile Club of Southern California for installation at its Los Angeles headquarters, and another section ripped up to make way for the All-American Canal, and so on. Countless cross ties literally went up in smoke as firewood for campers.

Now, only fragments of the Plank Road remain, protected under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management, and the route is designated as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern. In recognition of the Plank Road's stature as an important historic example of transportation technology, the State of California designated its ruins as a California Historical Landmark. Portions of the road also are considered eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

Remnants of the Plank Road may be seen at the west end of Grays Well Road, the frontage road south of Interstate 8. A Plank Road monument and interpretive display lie approximately three miles west of the Sand Hills interchange. This portion was preserved as a result of efforts by the Bureau of Land Management, the Imperial Valley Pioneer Historical Society, the California Off-Road Vehicle Association, and Air Force personnel. These groups worked together in the early 1970s to assemble a 1500 foot section from various locations in the dunes.

The Plank Road memorializes the determination and vision of those who forged the first automobile highway across the Sand Hills. Preservation of the old wooden road is the responsibility of all who use the desert. Time and circumstances have not been kind to this historic landmark. We invite you to help us ensure that the Plank Road reaches its centennial.

-- Source: California Bureau of Land Management

Read More

The Old Way: Historic U.S. 80 and the Wood Plank Road - by Tim Kessel for RIDER / December 14, 2018